Pearl educational

Pearl types

Akoya Cultured Pearls

The Akoya cultured pearl derives from oysters coming mainly from the southern and western portions of the Japanese islands.

The Akoya oyster, or pinctada martensi fucata, was first discovered in the mid 1800s and later successfully cultivated by the Japanese at the turn of the century.

Pearl farmers have three basic requirements to begin the process of forming an Akoya cultured pearl: a mature oyster ripe for seeding, a piece of mantle tissue from another healthy oyster, and the nucleus.

The mother oyster is the Akoya, a small and delicate mollusk whose shell grows to a diameter of only about seven centimeters at maturity after approximately three years of growth. Seeding takes place during the warmer months, from April to August.

Akoya oysters are harvested in winter. Despite the farmer’s diligence, there is no guarantee that a perfect, round pearl will be in any but a small percentage of the oysters. Some may contain no pearl at all. Others may contain pearls which are less desirable, some even unusable.

The harvested Akoya pearls, known at this stage as “hama-age,” are washed and sorted into broad categories. They are weighed in momme, an ancient Japanese unit equaling 3.75 grams, and then auctioned off to pearl processors.

Because of the large worldwide demand for necklaces, a high percentage of Akoya cultured pearls are strung into uniform chokers or graduated strands. The rest find their way into individual pieces such as rings, earrings, brooches, tie pins and other types of fashionable jewelry.

South Sea Cultured Pearls

Because of its scarcity, larger size and beauty, the South Sea cultured pearl is treasured as “the Queen of Pearls” and “The Pearl of Queens.”

South Sea cultured pearls may be easily distinguished from their Akoya counterparts by their larger size. Generally speaking, where the Akoya stops in size, the South Sea pearl begins. The Akoya cultured pearl usually ranges from 2mm to 9mm, the South Sea cultured pearl from 9mm to 16mm or, in very exceptional cases, even larger.

There are two basic groups of South Sea cultured Pearls: white and dark.

The White Group

The Dark Group

The dark group of South Sea cultured pearls derives from large, black-lipped pearl oysters scientifically known as pinctada margaritifera which live in the waters surrounding Tahiti.

The inside edges of this oyster are characterized by a blackish-green belt with traces of pink bursting through. Its nacre is usually a lustrous deep, dark green. Because of these characteristics, the bulk of any crop will inevitably contain bluish, grayish or brown-black pearls.

The value of any South Sea cultured pearl varies, as with the Akoya, according to its size, color, shape, luster, texture, thickness of its coating and surface smoothness.

A wide variety of colors and tints may be found in the cultured pearls of both the white and the dark groups. Distinctive coloration is one reason why South Sea pearls are so highly prized. Their shapes, too, differ as only a very few are perfectly round.

Because of their relative scarcity, South Sea cultured pearls command high prices throughout the world. It is an accepted rule of thumb that a single South Sea cultured pearl may cost about the same as an entire Akoya choker.

Freshwater Cultured Pearls

Freshwater cultured pearl may usually be distinguished from an Akoya or South Sea cultured pearl by its smaller average size, irregular shape and wider range of coloration.

In the thirteenth century, the Chinese first discovered that pearls could be cultivated using freshwater mussels. Mud, wood, bone and metal were employed as irritants to stimulate production.

These techniques were attempted in Japan but it was not until 1924 that the Japanese experienced any marked degree of success. By 1930 they were exporting to India, China and England.

Cultivating Freshwater pearls without the aid of a nucleus began in 1946. Since then, technology has enhanced yields and brought these pearls worldwide popularity.

Japanese Freshwater pearls are cultivated primarily in Lake Biwa, near Kyoto. However, due to deteriorating water conditions, both the quality and quantity of Biwa cultured pearls have seriously declined. China, nowadays, produces the largest volume.

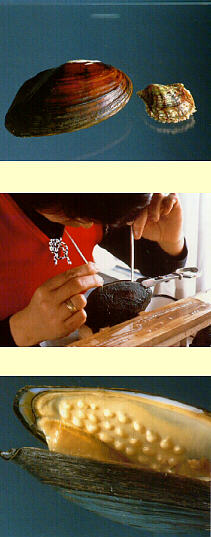

The mother mussels are called Ikecho, or hyriopsis schlegeli. They are much larger than Akoya oysters and after some fifteen years grow up to a length of 30cm and a width of 20cm.

Cultured pearl oysters from the sea are always seeded with both a piece of mantle tissue and a nucleus. But production of Freshwater pearls, if under 8mm, requires only the insertion of specks of mantle.

Suspended in cages at depths of 2m to 3m, the mussel is tended for three years until ready for its first harvesting. Ikecho mussels may be harvested a second or even a third time. There is no follow-up operation: the pearl sacs that were stimulated by the first operation are simply allowed to produce again. In the second harvesting, the mussel generally provides fewer pearls which are somewhat flatter in shape but which often have better luster and color. Growth slows and quality declines for the few mussels harvested a third time.

Today’s Freshwater pearl crops consist mainly of the smaller sizes, ranging from about 2mm to 5mm. The larger, irregular shapes known as crosses, doublets, triplets, sticks and dragons have become virtually extinct. The color ranges, too, are not as wide as before. Shades of white, pink, cream and light-to-dark orange predominate.

The usual criteria of size, shape, color, luster and cleanliness of the surface apply to the valuation of Freshwater cultured pearls.

There is no denying their widespread appeal as their variety allows designers and craftsmen to create exclusive, unique pieces of jewelry to suit many moods and settings.

Keshi Pearls

Keshis are created naturally in the soft tissue of most cultured pearl-bearing oysters and mussels. They are usually formed by the accidental intrusion of tiny natural organisms such as parasites, eggs, sand, fragments of shell, or small particles of mantle tissue that have detached themselves from the implanted nucleus.

After the larger cultured pearls have been removed from the mother shell, the keshis are carefully collected. They are regarded by the cultured pearl farmer as a valuable by-product of his harvest. The smallest keshis are not much larger than a pinhead, hence the origin of their alternate names: “seed” or “poppy” pearls.

Because of the painstaking effort the bigger keshis, from oysters bearing involved in drilling and stringing the very South Sea cultured pearls, may exceed small-sized variety of keshis, they are often 10mm. These rarer and very valuable pieces sent for processing to countries where labor are set into rings, pendants, earrings, brooches, costs are low. Also, due to being naturally and are even occasionally made into strands. produced (i.e., containing no man-made nuclei), keshi pearls are often ground up large or small, keshi pearls are and used for medicinal purposes in places appreciated by pearl fanciers worldwide such as India, Hong Kong and China.

The bigger keshis, from oysters bearing South Sea cultured pearls, may exceed 10mm. These rarer and very valuable pieces are set into ring, pendants, earrings, brooches, and are even occasionally made into strands.

Large or small, keshi pearls are appreciated by pearl fanciers worldwide and generally command high prices. and generally command high prices

Mabe Pearls

The mabe pearl oyster is found mainly in the tropical seas of Southeast Asia and in the Japanese islands around Okinawa. Its scientific name is pteria penguin, meaning “penguin wings.” The mabe oyster has a beautiful, rainbow-colored iridescence that ranges from light pink through dark rose to slightly bluish shades, often with a metallic luster.

From the early 1900s until today, many attempts have been made to cultivate round pearls from the mabe oyster, but all have commercially failed. However in the 1950’s, hemispherical pearls were successfully cultivated. Today, most of these cultured hemispheric pearls (or “half pearls” as they are more commonly known) do not come from the mabe oyster, but rather from the South Sea’s silver-lipped pictada maxima.

Several hemispherical, plastic nuclei are glued directly to the insides of the upper and lower shells of the mother oyster which then begins to secrete nacre over the intruders.

At harvest time the half pearl “caps” are stamped out and each nucleus is removed, leaving only a thin, hemispherical coating of hardened nacre which is sometimes only the thickness of a fingernail. This hollow cap is then filled with a resinous paste and closed on the bottom with mother-of-pearl.

Depending upon the form of the nucleus the farmer inserts into the mother oyster, other shapes of half pearls such as ovals, cushions, drops, three-quarters and hearts can result.

Cultivating half pearls often makes efficient use of oysters near the end of their life cycle and only a relatively short cultivation period is needed. It is also a much simpler process than cultivating spherical pearls. Thus, half pearls are rather inexpensive, even the larger ones ranging up to 22mm.

Imitation Pearls

Imitation pearls date back to antiquity, but were only mass-produced from the 16th and 17th centuries in Italy and France. They are, as the name suggests, entirely man-made. Imitation pearls in days gone by used a shell bead as a nucleus, covered by a coating of fish scales.

Today, more modern laboratory techniques are employed. Nuclei are made from either shell material, plastic, glass or porcelain. New synthetic materials, combined with sophisticated coating techniques, produce an imitation pearl that may often be mistaken, at first glance, for either a natural or a cultured pearl.

The most famous name in imitation pearls is “Mallorca” (or “Majorca”), from the Mediterranean island off the Spanish coast. There are many other production centers throughout the world, mostly concentrated in the Far East.

To differentiate an imitation pearl from either a natural or cultured pearl, experts employ a variety of methods such as measuring fluorescence under ultraviolet light, analyzing specific gravity or examining the surface by means of an electron microscope.

An easier method is to “bite” the pearl. Rub it gently between your front teeth. If the surface feels “sandy” it is likely to be a natural or cultured pearl. If it feels smooth and glossy, it is likely to be an imitation pearl.