World's Foremost Upscale Discounter of Fine Swiss Watches and Precious Jewelry Since 1969

educational

The History of Swiss Watches

Watch wearing from 1500-1969

Past Times

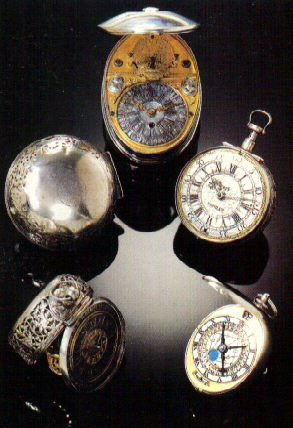

It began, appropriately, with an egg. Around 1500, Peter Henlein, a craftsman from Nuremberg, Germany, created the first watch by enclosing a timekeeping movement in a round portable case (an iron musk ball, writes one historian) and adorning it with a dial and hours hand. Henlein’s timepiece and others that followed were later dubbed “Nuremberg eggs” because of their shape.

So goes one version of the birth of watch-making. It has never been confirmed, and, like much watch history that followed, is the subject of some dispute.

Ovoid or otherwise, from Nuremberg or somewhere else, the first watches- and all their descendants up to the middle of this century depended on a simple but ingenious invention. It was a spring that, as it gradually unwound, provided energy that moved the timepiece hands, thus performing the same function as the weights that powered the clock atop the village church tower. This device came to be known as the mainspring.

The earliest watches were ornate, exorbitantly expensive contraptions that contributed more to their wearers’ social status than to their punctuality. They had no minutes hands, which would have been pointless on timepieces that could barely register the correct hour. Furthermore, they were a royal nuisance (and royalty were just about the only people who could afford them), needing to be wound with a key twice a day. People wore them around their necks or carried them in purses. (Elizabeth I of England, who lived from 1533 to 1603, reportedly bucked convention when it came to watches as she did in much else. She is said to have worn a “ring” watch that alerted her to the arrival of a pre-set hour by scratching her finger with a metal projection.)

Accuracy improved gradually through the 16th and first part of the 17th centuries. Then, around 1675, it made a quantum leap due to the second great invention in watch history, the “balance” or “hair” spring. The balance spring was an unprecedentedly precise way of regulating the oscillations of the balance. Most historians give credit for the invention to Christiaan Huygens of Holland. The balance spring made watches accurate to within an amazing 5 minutes a day. There would not be a comparable leap in watch accuracy until the first electronic watch, Bvlova’s Accutron (developed by the Swiss electrical engineer Max Hetzel), appeared in 1960.

Timekeeping improvements followed quickly during the century that followed. The first watches with a seconds hand appeared in the 1690s. The first chronograph, consisting of a seconds hand which could be stopped independently while the watch itself kept running, appeared in 1776.

One of the biggest events of the era, though, wasn’t the birth of an idea, but of an idea man. Abraham-Louis Breguet (1747-1823), just about everyone agrees, was the greatest watchmaker of all time.

Born in Neuchatel, Switzerland, he spent most of his life working in Paris, where he became the watch and clockmaking darling of the ancient regime before the French Revolution. When the conflict was over, he made amends with the victors and they, too, became his customers. He was watchmaker to European royalty and U.S. presidents (George Washington owned a Breguet. So did Alexander I. Marie Antoinette owned many, Napoleon and Josephine Bonaparte were avid customers, as were other Bonaparte family members.) Everyone wanted, to paraphrase an English baronet, writing a century after Breguet’s death, “to hold the brains of a genius in [his] pocket.”

Among Breguet’s inventions was the tourbillon, which compensates for the slight differences in timing a watch records when held in different positions. The tourbillon remains a much-coveted feature on expensive mechanical watches today. He also invented a watch that ran without winding for 60 hours. The perpetual calendar, so named because it automatically adjusts for the number of days in the month and for leap years, was another Breguet invention. It, like the tourbillon, is a sought-after feature on modern watches.

Thanks to a shockproofing device Breguet developed, the timepieces made in his 100-man workshop were more durable and reliable than any had been before. (The nearly 300 years that had passed since the Nuremberg eggs, whose fragility made the name doubly apt, had done little to make watches sturdier.) They also looked completely different from the elaborately decorated rococo styles that had been in vogue. Breguet’s watches had slim, graceful cases and simple faces. An engraving process called “engine turning,” yet another Breguet invention, gave the dials a rich, satiny finish. Even the watches’ hands were stand-outs, bearing elegantly tapered tips embellished, for greater visibility, with small open circles. Watch designers today still use “Breguet” hands to impart a look of elegance.

Breguet’s life bridged two eras in watch history. The first was one of hand craftsmanship catering to the wealthy few, an age Breguet epitomized with his exquisite, custom-made pieces. The second, already underway when Breguet died, would be increasingly dominated by mass production and mass demand, the hallmarks of the industrial Revolution.

The swelling urban population needed watches to keep the machinery of the burgeoning factories, and of city life in general, running smoothly. In 1825 came a dramatic event that accelerated the growth in demand for watches: The world’s first steam-operated freight and passenger railroad went into operation in England. Rail transport soon spread throughout Europe and America, and with it a need for portable timepieces.

The railway, in turn, led to the institution of standard time zones, first in the U.S. (in 1883) and then throughout the world. (Prior to that, there were nearly 300 local times in this country alone.) That made watches all the more desirable, since they now told the wearer not just the time at home but everywhere else in the world. World watch production increased by nearly 10 times to 2.5 million between 1800 and 1875.

About two-thirds of those watches were made in Switzerland, which in the late 18th century unseated England as king of the watchmaking world.

In the 19th century came the introduction of standardized, machine made parts in watch factories in Switzerland and the United States. The American company Waltham Watch Co. was an early pioneer of machine production. it and other U.S. companies produced timepieces of unsurpassed quality, and were the reason for America’s brief shining moment in watch history in the latter half of the l9th century. For a few years, American watchmaking was the envy of the expert Swiss.

It was the latter, though, who prevailed. Good as the Americans were at mastering machine production, the Swiss were better, with more versatile factories making a broader range of watches.

At the same time, the Swiss industry had honed its hand-crafting skills to their sharpest point ever. Companies such as Patek Philippe made lavish one-of-a-kind pieces for the rich and famous, including England’s Queen Victoria and Prince Albert and other crowned heads of Europe.

A new century brought a new type of timer. Well, almost new. The first wristwatches were probably worn in the early 19th century (although at least one expert claims Elizabeth I wore a little watch tied around her wrist with a ribbon, a companion, presumably, to her finger-scratching “ring” watch). in 1906, Cartier made a wristwatch for the aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont, who had requested a timepiece that would allow him to keep his hands free while flying his airships. In 1911 the company started producing the “Santos-Dumont” wristwatch for European high society, making it the first truly commercial wristwatch.

But it was not until World War I, when the military surrendered en masse to the charms of fumble-free time-telling, that wristwatches were taken up by the general public.

Somewhat reluctantly, as it turned out. Despite their blood-and-guts birth in the trenches, wristwatches were at first dismissed by many as uncomfortably unmasculine. Men and women alike often thought of them as a fad.

Within a decade most had changed their minds. By the late 1920s world production of wristwatches had surpassed that of pocket watches. The wristwatch’s appeal was not just convenience, but appearance. The new timers quickly developed a personality of their own, taking on shapes never imagined in the days of the pocket watch-tonneau, square (like the SantosDumont), baguette and tank- and decorated with a fanciful assortment of numerals, lugs and bracelets.

Switzerland remained the leader in watch production as Patek Philippe, Constantin, Audemars Piguet and scores of others converted their factories to wristwatch production.

As the decades passed, Swiss manufacturers set about miniaturizing for wristwatches all the Vacheron features and functions that had been available in pocket timepieces: chronographs, repeaters, calendars, tourbillons, self-winding and more.

They also made their watches increasingly accurate. just how accurate became apparent when, in 1962, NASA bought from a Houston jewelry store an Omega Speedmaster, subjected it to a battery of hellish endurance and accuracy tests, and found it fit to fly in a spaceship around the world, and eventually much farther. On July 20, 1969, when Apollo 11 made its historic lunar landing, the Speedmaster became the first watch on the moon.

But the Swiss Apollo triumph was short-lived. Within a few months watch technology would make a leap as giant as Armstrong’s. It would take place not in Switzerland, but in Japan.

Above: A watch by London clock and watchmaker Thomas Tompoin, circa 1690. It was offered for sale by the auction house antiquorium in 1993. Right: Christiaan Huygens

The Quartz Revolution

It’s Dec. 25, 1969, and the Japanese company Seiko has a Christmas gift for consumers everywhere. Sure, at $1,250, it’s a little expensive. But consider this: It’s accurate to within 5 seconds a day, and it never needs winding.

Seiko’s “Quartz Astron 35SQ,” proudly unveiled that Christmas Day, was the shot heard round the watch world: the start of a watch industry shake-up that would topple its long-time leaders and crown new ones. For the consumer it would mean nothing but good news: Timekeeping was easier and more accurate than ever before.

At the center of the maelstrom was a tiny synthetic quartz crystal which, when charged with electric current, vibrated thousands of times faster- 32,768 times per second, to be exact-than the balance wheel in a mechanical timepiece. Faster oscillations mean greater accuracy, whether the oscillator in question is the pendulum on a grandfather’s clock or a small piece of U-shaped quartz.

Although Seiko introduced the first quartz watch, the Swiss industry invented it. The Swiss completed the first quartz movement in 1967, the product of a cooperative effort among several companies. But they balked at putting the watch into production. Some believed quartz would prove to be a mere fad; others feared the cost of converting their factories would kill them. (They did eventually make the change, but too late to push the Japanese out of the spotlight.)

Five months after the Astron introduction, Pulsar, then owned by the U.S. firm Hamilton Watch Co., announced another horological surprise: a quartz watch that told the time with numbers rather than a dial and hands. This watch, the world’s first solid state digital model, showed the time by means of a light-emitting diode (LED, in industry parlance) that lit up the numbers when the wearer pushed a button. Due to technical problems, the watch did not make it to market until 1972. When it did, it was a hit despite its lordly $2, 100 price tag (or perhaps because of it-the watch was sold in posh jewelry stores such as Tiffany’s and was a real status symbol). By 1972 more than 50 companies were selling LEDs in the U.S., at prices that dropped within a few years to a mere $20 or less.

The LED didn’t last long. By the late ’70s a new type of digital, the liquid crystal display (LCD), had taken over. Unlike the LED, the LCD told the time all the time, not just when the wearer pushed a button. LCDS, produced largely by a burgeoning Hong Kong watch industry, became plentiful and cheap, even cheaper than the LED.

The digital craze hit its peak in the mid-’80s when, worldwide, companies were turning out more quartz digital watches than they were quartz analog ones. The frenzy soon ended. A glut developed, prices continued to drop, and the glamour and mystique that had so attracted digital watch customers a decade before disappeared.

The trend toward quartz, however, got stronger by the minute. Analog quartz watches, which leant themselves much better than digitals to stylish design, ascended to a new status. Watch companies brought out a bevy of elegant quartz analog models, slimmer than watches had ever been thanks to the compactness of quartz movements. In 1979, Concord took skinny to the extreme when it launched the Delirium, just 1.98mm thick.

Furthermore, quartz, with its accompanying micro-circuitry, made it possible to provide an amazing array of functions- a chronograph, or stopwatch function; a lap timer, to store the different times it takes to run the laps in a race; a countdown timer, which keeps track of the time before a race begins; and many others. All were as accurate as anyone could want.

Today, of course, quartz continues as king of the watch world. And until someone invents an atomic clock for the wrist, it’s likely to keep its throne

The Counter-Revolution

The Mechanical Strikes Back

After quartz technology through the watch industry in the ’70s, nearly everyone in it left the wind-up watch for dead. Little did they know that even as quartz watches waxed and wind-up models waned the stage was being set for a mechanical watch comeback.

It began in the ’70s when a few prescient entrepreneurs noticed a new phenomenon: The public was beginning to be interested in vintage wristwatches. These dealers started paying some very nice prices for old watches that a year or two before would have had value only as scrap; then they resold them for even nicer prices.

The trend ballooned and by the early ’80s the major auction houses were holding sales devoted exclusively to vintage wristwatches. Prices rocketed, especially for pieces made by the top echelon of Swiss manufacturers. Complicated pieces, including chronographs, perpetual calendars, minute repeaters and the like, brought the highest prices of all.

Several factors drove the boom. First, as quartz became ever more common, people saw that mechanical watches were threatened with extinction. Every year they became rarer and hence more valuable. The triumph of quartz spurred demand for vintage mechanicals the same way the triumph of the wristwatch had many years before created a collectibles market for old pocket watches.

Another factor: A vintage wristwatch was the ideal accessory for the proud ad executive or arbitrageur who was making it big in the fast-track’80s. A fine old wristwatch with a big Swiss name proved you were not just rich but also gifted with a certain amount of savoir faire.

Then, of course, there was the vast amount of money being made during the ’80s not just in the U.S. but in Asia and Europe. Collectors and speculators all over the world poured their millions into watches just as they did into impressionist paintings.

It was just a matter of time before watch companies realized there would be eager customers for new mechanical wristwatches as well as old. In the late ’80s Swiss companies started to bring forth bevies of luxury mechanical watches, a trend that has been gaining force every year since. Some are skeleton models that display their charmingly old-fashioned innards through a transparent dial or case back. Complicated watches, especially chronographs, are flourishing. So are automatic, or self-winding watches.

Companies like Rolex and Patek Philippe, which have stayed true to the mechanical throughout the quartz era, today enjoy record sales. Mechanical models now have unprecedented prestige. Why else would the Swiss company Blancpain boast: “Since 1735 there has never been a quartz Blancpain watch. And there never will be”?

The mechanical revival has been a windfall for the Swiss industry. Between 1988 and 1990 Swiss production of mechanical watches grew 70%. Last year, half of the country’s watch revenue came from mechanical models, although only 13% of the watches it produced were mechanicals.

In the meantime, the auction market, except for one major decline just before and during the recession of the early ’90s, has continued to soar, further fueling the mechanical boom. Just last October a world record was set in Geneva for the highest dollar amount ever paid for a wristwatch at auction. It was a Patek Philippe world timer gaveled off by Antiquorum, and it brought an eye-popping $790,000. (Valued in Swiss francs the watch was second to a platinum Patek sold some years earlier.) And in June of this year, Patek Philippe bought one of its own watches at Sotheby’s in New York for $519,500, setting a record for a Patek sold at auction in this country.

The Automatic

The Watch that Winds Itself

Since the revival of the mechanical watch in the late ’80s, one special of mechanical has become a fast favorite among timepiece aficionados. It is the automatic, or self-winding watch, whose allure comes from its combination of traditional mainspring-and-balance-wheel technology with the convenience of no winding. Nearly every company that makes mechanicals offers automatic models.

But the development of the self-winding watch was anything but automatic. In fact, it took more than a century and a half. The concept was invented around 1770 by the Swiss watchmaker Abraham-Louis Perrelet, a teacher of the great Abraham-Louis Breguet and a well-known craftsman in his own right. In Perrelet’s day, winding one’s watch was a bit of a pain, as all watches were wound with keys, which were easily misplaced Perrelet’s idea was to fit onto the watch movement a, rotor that swiveled in a 360-degree arc and, as it did so, wound the watch’s mainspring. The happy watch owner could, presumably, forget the tiresome task of winding his watch and throw away the key forever.

But there was one glitch: The rotor moved only when the watch moved. And in the case of pocket watches, that was not very often not often enough, anyway, to keep the watch ticking.

Breguet and other Swiss watchmakers tried to develop improved self-winding movements incorporating weights rather than a rotor, but to little avail. Insufficient power remained a problem; so did the noise of the weights hitting the buffers. The automatic remained a non-starter.

It wasn’t until watches moved from pockets to wrists after World War I that self-winding had a chance. John Harwood, a British soldier, realized that wristwatches were subject to much more motion than pocket watches. He dusted off the old idea of a self-winding movement and applied it to a wristwatch.

Harwood was inspired less by the inconvenience of daily winding than the fact that, during the rigors of trench warfare, the hole that held the winding stem allowed dirt to enter the case and damage the movement. His stemless automatic wristwatch (the wearer set it by rotating the bezel) was patented in 1923 and went into production in 1926.

It was a nice try. It was not, however, the long-sought solution to the self-winding quandary. Harwood’s watch used an oscillating rotor that swung in a 130-degree arc, stopped at either end by a buffer. As the weight hit the buffers, it shook the movement, and, over time, damaged it.

Rolex finally met the 160-year-old challenge. It did so by studying the history books. In 1931 it introduced a watch with a rotor like Perrelet’s, which provided plenty of energy to wind the mainspring while leaving the movement unshaken. It was called the Oyster Perpetual, an addition to its line of water-resistant Oyster watches, introduced in 1927.

Automatic winding became a much coveted staple of Swiss luxury watches until the quartz age. Now that mechanical watches are back, Swiss firms are working non-stop at launching new automatic models. They range from thick, masculine “high-mech” looks loaded with sub-dials and push pieces to elegant, streamlined dress versions. Some collectors’ editions come in special boxes with rotating holders that keep them in perpetual motion, always wound up and at the ready. Many show off their swiveling rotors through a window of see-through synthetic sapphire. And why not? Given the long effort to perfect self-winding technology, they have plenty of reason to be proud.

Modern Masterpieces

When Marie Antoinette’s lover (who was a member of her palace guard) wanted to impress her he ordered for her something sure to knock her silk stockings off. It was a watch that could not only tell the time, but chime the hours, show the difference between solar and mean time, keep track of the date, even during leap years, and much else.

Its multiplicity of extra functions, called “complications,” make the Marie Antoinette watch, produced by the workshop of the great Abraham-Louis Breguet, one of the most famous timepieces ever made. (The Queen, beheaded 27 years before the watch was completed in 1820, never got to revel in its glory. Nor can we. In 1976 it disappeared after a looting of the museum in Jerusalem where it was kept. Its whereabouts now is one of the great mysteries of the watch world.)

Earlier this century complications were at the heart of a horological duel between two rich watch collectors. It started when auto magnate James Ward Packard commissioned Patek Philippe to make him the most complicated- watch in the world. In 1927, he plopped down $16,000 for his new treasure, so intricate it even showed the star-lit sky exactly as it appeared from his bedroom window in Warren, Ohio. (In 1988 Patek Philippe purchased the watch from the American Watchmakers institute, to which it had been donated, for $1.3 million.)

When rival collector Henry Graves Jr. heard of Packard’s triumph, he asked Patek to make him an even more complicated watch. The 900-part timepiece took seven years, until 1933, to complete, and cost $75,000.

It remained the most complicated watch in the world until 1989, when Patek once again outdid itself with Calibre ’89, a grapefruit-sized wonder with a record 33 complications. Patek auctioned it off in April 1989 for $2.7 million, the most ever paid for a timepiece at auction. Calibre ’89 made one thing very clear: Complications remain the ne plus ultra of the watchmaker’s art, more valued now than ever before. About 95% of the complicated watches made in Switzerland are the work of craftsmen in the serene Vallee de Joux. There, in the tiny villages that dot the valley, watchmakers have been specializing in complicated movements for more than 200 years, passing down their skills from father to son.

Probably the best-known type of complication is the chronograph. Not to be confused with a chronometer, which is a timepiece that meets certain rigorous standards of accuracy, a chronograph measures intervals of time. It is the same as a stopwatch function. Chronos show elapsed time by means of a center seconds hand, a small subdial or subdials on the watch face, or both. Some chronos are able, by means of subdials called minute or hour registers, to keep track of very long periods of time-up to 12 hours. Most chronos are started and stopped by pushing buttons on the side of the watch case. Often, one button is used for starting and stopping the time, another for returning the hand to zero

(12 o’clock).

A split seconds chronograph, also called a rattrapante (French for “catching up”), is used for measuring two or more succeeding intervals of time, as when, for example, you are timing a race with several runners who cross the finish line at different times. The words “split second” refer not to the accuracy of the chronograph, but to the fact that its seconds hand (really two superimposed seconds hands that run together) can, in effect, be split into two hands.

Here’s how it works: At the start of the race the wearer pushes the chronograph button, setting the two superimposed hands in motion. As the first runner finishes the race, the wearer pushes a supplementary button stopping the top seconds hand. The bottom hand keeps moving. The wearer records the first runner’s time, then pushes the supplementary button again, causing the stopped hand to jump forward and catch up with the still-moving bottom hand. When the second runner finishes, the wearer once again pushes the supplementary button to stop the top hand, records the second runner’s time, and pushes the supplementary button to once again make the top hand jump ahead to join the bottom hand. The wearer continues the process until all the runners have finished.

The single-hand split seconds chronograph, like the split seconds chrono, is used for timing successive intervals of time. The wearer stops the chronograph hand when the first runner finishes the race. When he pushes the button to start the chrono again, it jumps forward to where it would be if it had never stopped, thus allowing the second runner’s time to be measured without interruption.

Many chronograph watches have numerical scales just inside the perimeter of the watch face that enable a center-seconds chronograph hand to give information other than elapsed time. A tachymeter (or tachometer) scale allows the wearer to measure the speed at which he travels over a measured distance, a measured mile on the highway, for instance. The wearer starts the chronograph when he passes the starting point and stops it when he passes the finish. He can then read his speed in units (in this case, miles) per hour off the tachymeter scale. That number represents the number of seconds of travel divided into the number of seconds in an hour.

A telemeter scale allows the wearer to use his chronograph to determine an object’s distance from him by measuring the amount of time it takes sound to reach him. One application of a telemeter would be determining the distance of ‘ a storm. The wearer starts the chronograph the instant he sees a flash of lightning, then stops it when he hears thunder. He can then read the storm’s distance from him, in miles, on the telemeter scale. The dial’s markings are based on the fact that sound travels at a distance of 1, 1 29 feet per second and there are 5,280 feet in a mile. A time of 5 seconds would mean the storm was 5,645 feet away; the chronograph hand would show a distance of just over I mile on the telemeter scale.

A pulsimeter scale, also found on some chronographs, is used for measuring pulses. The wearer starts the chronograph and simultaneously begins counting the pulse. When the count reaches 30 (most pulsimeters are based on 30 counts) he stops the chronograph and reads the pulse rate per minute from the pulsimeter scale.

Calendars are another type of complication. Some show the date through an aperture on the watch face; others by means of a subdial, with a numerical scale showing dates from 1 to 31; still others with a center hand that points to a date scale around the perimeter of the watch face.

A particularly prestigious feature is the perpetual calendar, which adjusts automatically to account for the different lengths of each month, including February during a leap year. Many perpetual calendars are mechanically programmed to be accurate until the year 2,100, when they will need to be adjusted.

Moon-phase indicators, as the name implies, show what phase the moon is in on a particular day. They do so by means of a disk bearing pictures of two moons that rotates day by day beneath an aperture in the watch face. As it does so, successively larger or smaller sections of the moon are visible through the aperture.

An equation of time indicator shows the difference, by means of a subdial, between mean solar time (the conventional time shown on timepieces) and apparent solar time (the time that would be shown on a sundial).

Second time zone indicators let the wearer know what time it is in a different time zone. Some watches with this feature have two faces for showing two times. Others have an independent hours hand that indicates the second time on the watch’s regular hour scale.

Repeaters let you know what time it is without looking at your watch. When you push the repeater button, you hear the time chimed out by hours, quarter-hours, and, in the case of a minute repeater, minutes. The repeater was the first complication ever invented (the Englishman Daniel Quare patented one in 1687), a solution to the problem of watch wearers, in the days before electricity, being unable to read their timepieces at night. A grande sonnerie (big ring) sounds the quarter hours with chimes for the hour followed by the quarter. The petite sonnerie (small ring) also chimes the hours and quarter-hours, but the latter are not preceded by the hour chime.

In the past few years some companies have combined several complications in a single wristwatch, creating what is known as a grande complication. Watches that have a chronograph, repeater and calendar function fall into this very elite category, which, until 1990, was occupied solely by pocket watches.

In addition to the features listed above, all of them embellishments, so to speak, on straight timekeeping, watches now come equipped with a host of non-horological functions sometimes referred to, loosely, as complications. These include compasses, thermometers, pedometers, depth sensors, altimeters and others.

© Capetown Watch & Diamond 2022